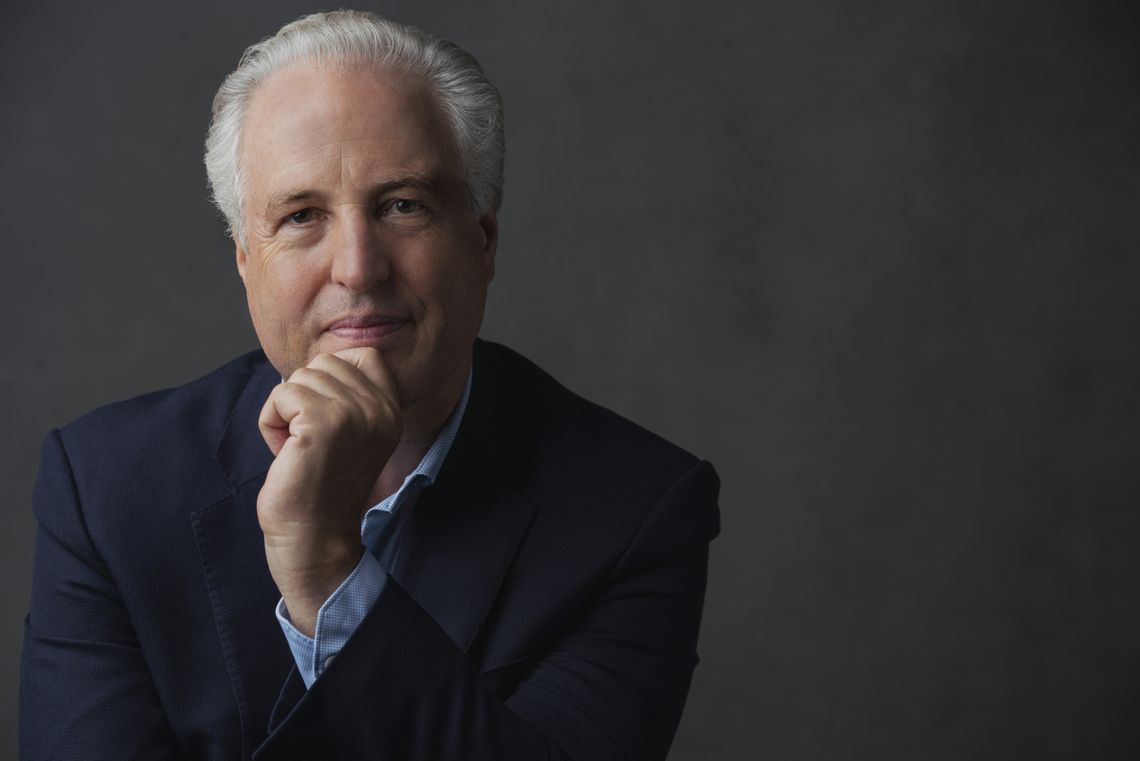

Manfred Honeck is the new Honorary Conductor of the Bamberg Symphony

Conductor Manfred Honeck has been a regular guest at the Bamberg Symphony for 32 years. In November 2023 the orchestra appointed him Honorary Conductor. This makes Manfred Honeck - after Eugen Jochum, Horst Stein, Herbert Blomstedt and Christoph Eschenbach - the fifth conductor to receive this honour.

Honorary conductors rightly deserve a special place in the chronicle of an orchestra. For it is not uncommon for them to stand for an entire era, having a great impact on the orchestra's reputation beyond their tenure.

Manfred Honeck's collaboration with the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra began in the 1980s, just at the start of his conducting career. He also made his first ever CD recordings in Bamberg in the early 1990s. Here is what Manfred Honeck had to say about his relationship with the orchestra: "I look back with gratitude on the many years in which I have worked with the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra time and again. They supported me significantly even as a young conductor, which still means a lot to me. I hold the orchestra and its quality in the

highest regard, and it always gives me great pleasure to make music together. I am honoured to be able to join the illustrious circle of honorary conductors as 'Benjamin'."

Since then, there have been a total of 109 joint concerts, most of them in Bamberg. The Bamberg Symphony Orchestra can also be heard regularly at the International Wolfegg Concerts, of which Manfred Honeck is Artistic Director. With the title of Honorary Conductor, the orchestra would like to officially honour, further

develop, and intensify the very fruitful, decade-long partnership with Manfred Honeck.

Musical Master Architects

The Bamberg Symphony and its Honorary Conductors Herbert Blomstedt and Christoph Eschenbach

by Wolfgang Sandner

He’s not on the staff, and he’s not a volunteer. He has no obligations or special responsibilities. He can’t even expect a vote of thanks – as he might for charity work. And yet, for any maestro, it’s the ultimate accolade: »Honorary Conductor«. So coveted, in fact, that many an ensemble baulks at bestowing it. Which is why the few it has been bestowed on find themselves in a small, select club, whose members have achieved something exceptional: moulding an orchestra, audibly raising its artistic game, sticking by it, supporting it through tough times, and staying loyal to it literally come what may. That has quite an effect, no question.

Any discussion of an outstanding ensemble’s distinctive characteristics, the artistic profile which sets an orchestra apart, and the personalities who have shaped it, inevitably returns to the same handful of holders of this title – which is usually conferred at the end of their tenure, though not necessarily the end of the partnership. In the annals of any orchestra, honorary conductors rightly occupy a special place – not uncommonly, they stand for an entire era, whose effect lingers long after their actual tenure – influencing image, reputation, sometimes even genetic make-up. In this connection, two orchestras and their Honorary Conductors deserve special mention: the St. Petersburg Philharmonic, Russia’s oldest orchestra, and the Philadelphia Orchestra. For half a century – from 1938 until his death in 1988 – Yevgeniy Mravinsky headed the orchestra of the city of his birth, moulding it into the Soviet Union’s foremost symphonic corps. There is surely no match in all music history for such a long, uninterrupted partnership between one conductor and one orchestra. Which is why the Philharmonic was rightly – correctly, even, in dynastic terms – dubbed ‘Mravinsky’s Orchestra’. Or ‘Shostakovich’s Symphony’ – after all, Mravinsky’s effortless authority as Principal Conductor, and the Petersburg Orchestra’s artistic excellence, benefited no other composer more than Dmitri Shostakovich, whose Fifth, Sixth, Eighth, Ninth and Tenth Symphonies were all premiered on the River Neva. Much the same can be said of the Philadelphia Orchestra. The fact that it has maintained its characteristically brilliant ‘wide-screen sound’ for so long must have something to do with the paucity of its Principal Conductors: just eight in an almost 120-year history. The third and fourth, Leopold Stokowski and Eugene Ormandy – one of Polish-Irish descent, the other Hungarian – presided for no less than 70 years in total over this permanent member of the US’s »Big Five« symphony orchestras. Both, it goes without saying, were also Honorary Conductors. During his last years on the podium, Ormandy could probably just blink, and the players would know precisely what he meant and when to come in. When the Italian conductor Riccardo Muti took over from Eugene Ormandy in 1980, he must have known intuitively that there was no question of simply imposing his own musical agenda. Moving into his predecessor’s dressing room at the Academy of Music, the Orchestra’s old home on Locust Street, he refused to replace Ormandy’s name plate on the door – at least, according to an unverified if tenacious legend. Muti was clearly unwilling to let a simple change of name plate disturb forty-four years of unbroken tradition. There are countless similar stories of conductors who became formative figures for their orchestras – as orchestral trainers, shapers of sound and, not least, public symbols of an artistic attitude. Riccardo Muti’s successor in Philadelphia was Wolfgang Sawallisch, who also exerted a lasting influence on the Orchestra, through his combination of supreme artistry and pragmatism, the latter a quality traditionally much prized locally. One concert above all stays in the memory – it threatened not to take place at all, with several players gridlocked in traffic by bad weather. Without batting an eyelid, Sawallisch kept the audience onside and whiled away the wait, by sitting down at the piano and accompanying singers in opera arias. It’s just the kind of thing you might also expect of Christoph Eschenbach, the Bamberg Symphony’s quite exceptional Honorary Conductor. Eschenbach, who incidentally was Sawallisch’s successor in Philadelphia, is an exceptional conductor and orchestral trainer, and no less accomplished as a pianist, chamber musician and teacher. It’s a matter of great regret that his packed conducting schedule has left him little time so far to exercise his other musical talents as fully. He too would have no difficulty in going solo and delighting his audience with Chopin nocturnes, Mozart arias or lieder by Aribert Reimann – not just to fill an unexpected delay to a concert caused by traffic, which in any case is much less of a worry in Bamberg than in big US cities. As Honorary Conductor of the Bamberg Symphony, Christoph Eschenbach is exceptional in another regard, too – like Herbert Blomstedt, he has never been the Orchestra’s Principal Conductor. As a pianist, Eschenbach’s partnership with Bamberg goes back as far as October 1965; his conducting debut came in 1977. Since then, not only has he led the Orchestra repeatedly in Bamberg itself, he has also taken it on successful tours to the United States, South America, Japan, France, Austria, Hungary, the Baltic and, in 2016, to Oman, among other destinations. During this half century, he has presided over the Orchestra on nearly two hundred occasions, and they enjoy a genuinely deep artistic friendship. So it was only natural that two years ago, on being awarded the renowned and highly valuable Ernst von Siemens Music Prize, Eschenbach appeared in concert with the Bamberg Symphony in Munich’s Herkulessaal. This long-standing partnership with Christoph Eschenbach has been fruitful for the Bamberg Symphony in many different ways, and has shaped the Orchestra. Without doubt, the Bambergers have gained greatly from the extraordinary career of this pianist and conductor, born in 1940 in Breslau (now Wrocław), and a protégé of Herbert von Karajan and George Szell. From beginnings in provincial Germany, it has taken him on a wide-ranging journey through the most varied venues of the music world to mastery of his profession: from Houston, Chicago, Philadelphia and Washington to London, Zurich, Paris, Hamburg, Milan and, in the near future, to Berlin’s Konzerthaus, as its next Principal Conductor.

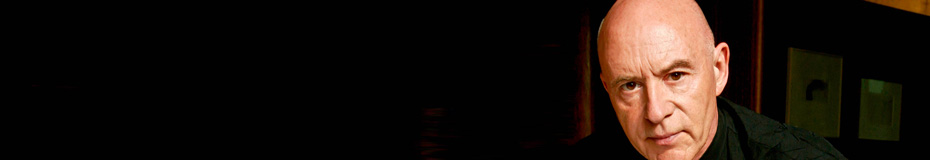

But it is Bamberg, above all, which has benefited from Eschenbach, a renaissance man to whom eighteenth-century music is as familiar and beloved as that of the twentieth and twenty-first. Must one have performed avant garde music, to be a better interpreter of older repertoire? Pierre Boulez thought so, and he had reason to know. Anyone who has mastered Ligeti’s sonorities and Stockhausen’s rhythms, so this argument goes, is better equipped for the classics – and as evidence, one need only cite Christoph Eschenbach. Listening to him in much-played Classical and Romantic music, above all, one always feels that his structural analyses of contemporary works have had a beneficial effect in older music – for instance, in Schumann’s Symphonies, which seldom sound as lucid, transparent and sheerly beautiful as they do under Eschenbach. His recording of all four Symphonies must rank as one of the outstanding achievements of the partnership between Eschenbach and the Bamberg Symphony. Meanwhile, his work with the Orchestra amounts to something very like a virtual encyclopaedia of music, starting with Mozart concertos directed from the keyboard, taking in Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms and Bruckner, up to Gustav Mahler and far into the music of tomorrow. Among its undoubted glories are cello concertos by Shostakovich and Lutosławski, with Heinrich Schiff as soloist, and Alfred Schnittke’s Concerto Grosso No.5 with the violinist Gidon Kremer. There are signs that this encyclopaedia will grow even more quickly in the near future: after thirty years as Musical Director of several leading American orchestras, Christoph Eschenbach is shifting the focus of his activity back to Europe. So Bamberg too can look forward to yet more of this close artistic collaboration with Eschenbach. The relationship with Christoph Eschenbach has been a constant in the Bamberg Symphony’s past and present – as has that with another great conductor, who like Eschenbach is highly regarded by every orchestra of standing in the musical world. Herbert Blomstedt was born in the US to Swedish parents in 1927, which makes him the world’s oldest active conductor today. Throughout his long career, launched in 1954, wherever he has worked, including as a regular guest conductor, he has left a lasting impression as a pre-eminent orchestral trainer. Conductors who have taken over orchestras from him – such as Michael Tilson Thomas, still with the San Francisco Symphony, or Riccardo Chailly at the Gewandhaus Orchestra in Leipzig – have always found them to be trained to perfection and highly motivated. No wonder, then, that Blomstedt has been made Honorary Conductor of almost every orchestra he has worked with for a substantial length of time: in Tokyo and San Francisco, where he was the first Honorary Conductor, in Stockholm, Copenhagen, Dresden, Leipzig, and finally in 2006 by the Bamberg Symphony, which he conducted for the first time in 1982 and with whom he has, like Christoph Eschenbach, notched up some two hundred concerts, including many guest appearances abroad. Of course, the main reason for Blomstedt’s high reputation among symphony orchestras the world over is artistic. He is an exacting musical interpreter, who never luxuriates in mere sound but aims for clearly graspable structure – which pays special dividends in large orchestral spans such as the symphonies of Anton Bruckner, or the works of Jean Sibelius, with their almost organically proliferating forms. It’s almost as if Bruckner’s »projection of the symphonic idea into the monumental” can only be realised by Blomstedt’s perfect ensemble and economical beat. Yet behind everything Blomstedt accomplishes with an orchestra like the Bamberg Symphony, you sense his imperative expressive will, which in turn conceals a strict work ethos. Of course, what’s truly astonishing is that Blomstedt has been able to achieve such extraordinary musical results without any of the behaviour or any of the traits which the public believes are essential in a conductor. Few people are prepared to credit the archetypal conductor with the virtue Blomstedt has come to stand for: tact. They imagine conductors, especially great ones, as implacable, eccentric, unfailingly extrovert show-offs revelling in their power. They’re supposed to be Prussians, strategists, a rock in any musical storm. Herbert Blomstedt, though, is nothing like this shallow mirage of his profession, but rather its exact opposite: neither histrionic nor vain, he is the composer’s faithful advocate, a friendly, highly likable colleague to boot, and a great artist. Is there anyone in Bamberg who doesn’t know that, and doesn’t count on him for the future? (translation: Dr. Nick Morgan)

»Like an Old Master in a Gilt Frame«

A portrait of Herbert Blomstedt

»An old love constantly renewed«

A portrait of Christoph Eschenbach